Before diving into today’s missive, let’s think about amber. You know, the yellowy, fossilised tree sap at the core of the Jurassic Park story. It’s been an important commodity for thousands of years and used to be prized for its clarity and flawlessness.

In the 19th century, it became possible to synthesize amber. You can test for whether a sample is real or artificial, but it tends to damage or even destroy the sample and is time-consuming and expensive to do at scale.

As a result, a specimen of amber which looked like it had no flaws – the top tier stuff – was immediately suspected of being fake, and samples which had visible flaws and were obviously natural became more prized and potentially more valuable than perfect ones (though forgers got involved in other subterfuge). Real, natural and flawed became somewhat more valued than pristine.

Fake vs Real content

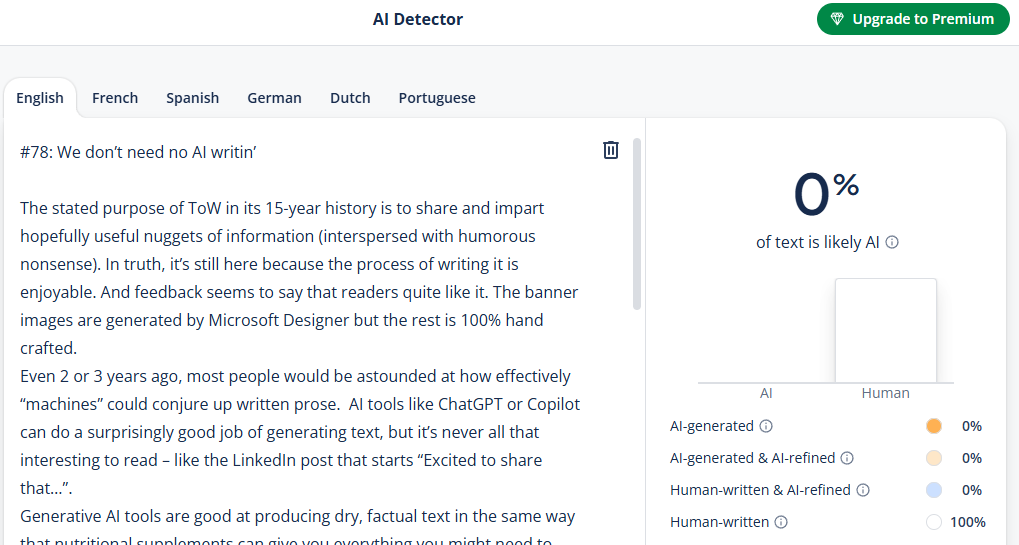

A parallel is perhaps looming in the world of Generative AI and the content it produces. It’s now so easy to rattle out a 1,000 word blog post with illustrations and even references to other sources, why should you believe that anything is produced by a person?

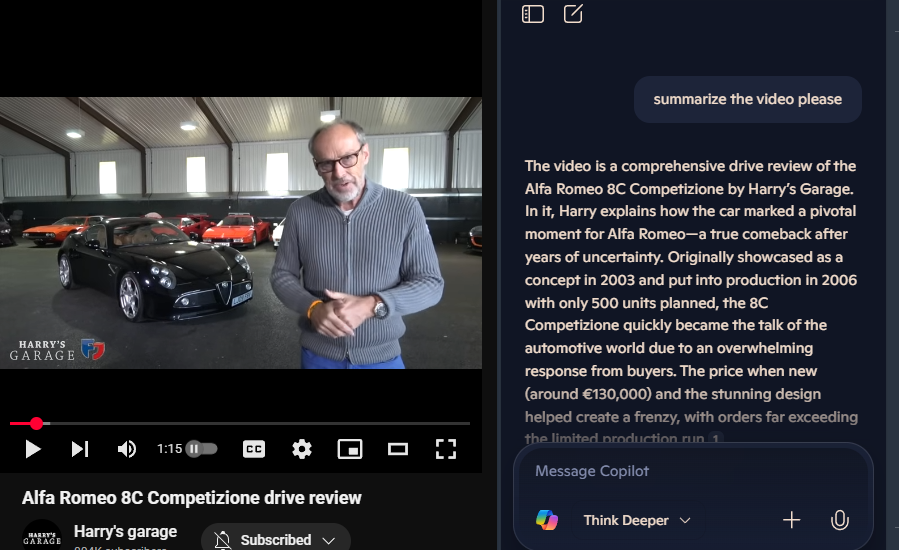

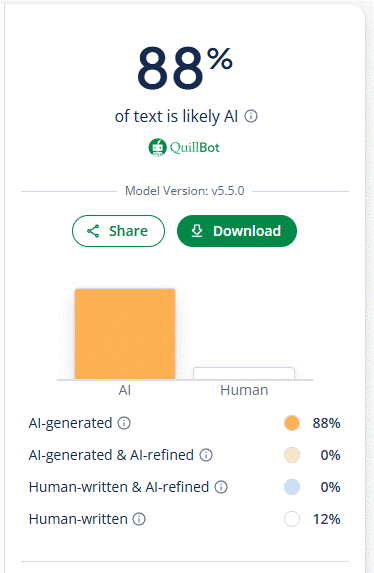

Try using a tool like Quillbot’s AI Detector – paste some text in there and it’ll give you a score. Even supposedly trustworthy LinkedIn “Top Voices” are cranking out stuff that is largely AI-written. In some ways, it doesn’t matter – if the author isn’t a very good writer but they have good ideas, these tools could help them form the basis of a post.

But if someone is sending you email that is AI-written, sure it’s maybe more efficient from their perspective, but what does that say about how they view their interaction with you? Even using AI tools can get you in hot water.

Will AI start infecting itself?

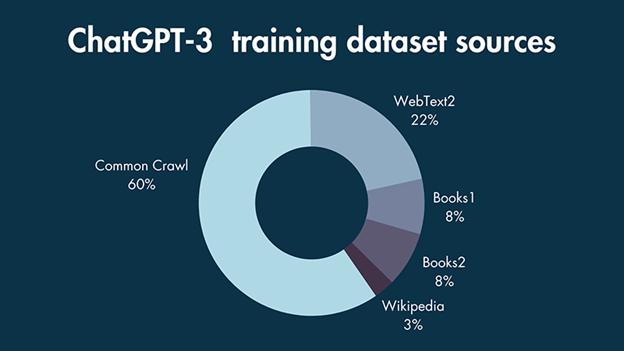

If much of the data that was used to train ChatGPT came from online sources, and even with models dipping into more traditional, copyrighted materials, at what point will AI start feeding on its own output?

Source – Style Factory Communications

“AI Slop” is a term coined for the huge volume of AI-generated material that is of inherently low-quality (regurgitation of other people’s work, or stupid visuals which are nearer to Jackass than Day of the Jackal).

Internet search is starting to get less useful as AI-generated guff displaces real results. Two and a half years ago, an AI researcher from King’s College, London, was quoted in the MIT Technology Review as saying, “The internet is now forever contaminated with images made by AI.”

Research suggests that even 9 months ago, nearly 25% of corporate press releases were AI-generated. It might be possible to tell via Quillbot-type sniff-tests that something is written by AI, and moves are afoot (like Google’s SynthID) to mark stuff as having been AI-created. As creation tools get more sophisticated, however, will there be an arms race to know what’s real and what isn’t?

What and who to believe is getting harder

We’ve been living in a world of misinformation for at least 10 years; from shadowy organizations harnessing data in order to target a specific message to people on social media, all the way up to conspiracy theories where nobody apparently gains other than to shake things up. In civilized societies, we usually have at least one source of truth that we can rely on, rather than believing online whackos.

Leaving aside some lunatics who deride “Mainstream Media”, trustworthy outlets can be relied on to pass on balanced news coverage, and might even have teams like BBC Verify to cross-check sources.

The excellent (and 100% human generated) Rest Is Entertainment podcast recently talked about Google Flow, a tool using their Veo 3 video & audio rendering technology.

source – YouTube – Impossible Challenges (Google Veo 3 )

Richard theorises that, very shortly, most short-form video content (like adverts or TikToks) will be AI-generated and that anything human-created might become premium.

AI tools can be thought of as akin to a calculator being used by an accountant or a digital easel being used by a great artist. The positive spin is that creative people will use these tools to make it easier: just as bedroom musicians can now produce hit singles that would have taken weeks of studio production, smart people with good ideas will use these tools to develop and release new content more directly.

Until the 1990s, it was seen – by some – as acceptable to put ground up bits of animals into feed given to (herbivorous) cows being reared for meat.

When next-gen AI tools are trained, let’s hope they know how to differentiate the nonsense that’s been generated over the last couple of years or they may get poisoned by the slop their predecessors created.